Happy In Theory

This is the short story of my long search for a stable academic home. There is a lot of success and a lot of pain here, and no happy ending.

Future historians of science will debate a paradox. Even though departments of Psychology are more often situated in faculties of life science than humanities, even though some of the world’s most prestigious departments have their commitment to science embedded in their name (they are departments of Experimental Psychology), and even though the primary guiding principle of world’s largest psychological organisation is to “build on a foundation of science,” the category ‘Theoretical Psychologist’ does not exist. Psychology is self-conscious about its identity as a science and theory is intrinsic to the older sciences Psychology aims to emulate, but if you call yourself a theoretical psychologist then other psychologists express confusion. “Do you mean Philosophy?,” they ask. In Physics you can get a Nobel Prize for theory and many people have done. In Psychology, I have learned, you can barely get a job.

My undergraduate degree was in mathematics and afterwards I wanted to see the world. I taught English in Bolivia. Back in the UK I worked in e-learning, then I taught English again, now in Italy. I started to read popular science books about human nature, and became fascinated with the theory of natural selection.

Charles Darwin’s big idea is not just an empirical finding, it’s also a powerful tool for explaining why living things are the way they are. I read Darwin’s lament that his contemporaries wanted only data, and it resonated. “About thirty years ago there was much talk that geologists ought only to observe and not theorise; and I well remember some one saying that at this rate a man might as well go into a gravel-pit and count the pebbles and describe the colours. How odd it is that anyone should not see that all observation must be for or against some view if it is to be of any service!”

I was especially inspired by the idea that evolution could help us understand the mind. Darwin showed how design in nature has a natural origin, and that discovery justifies a very powerful tool: reverse engineering. We reverse engineer all the time with the products of human design, like self-assembly toys. What’s this bit for? Maybe it goes here. The theory of natural selection gives reason to do the same with life. What’s that long beak good for? Maybe picking up insects. Let’s find out. This idea, to reverse engineer the living world, is sometimes called ‘adaptationism’. I learned that some psychologists were using adaptationism to try to understand the mind, and I was intrigued.

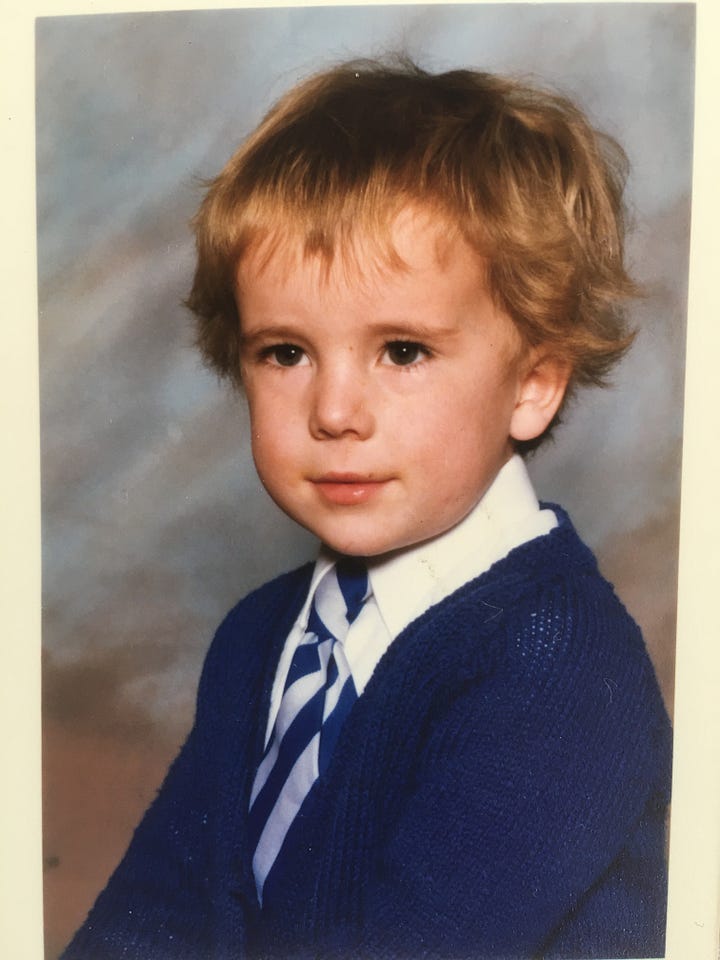

So the little money I’d saved while working, I spent on an MSc in the Evolution of Language & Cognition. I enjoyed it and did well. I got funding to do a PhD on adaptationism and human communication. Meanwhile I moved in with a girlfriend for the first time, and I found a new hobby, dancing the lindy hop. I was bullied at school and I felt lost after university, but now I had direction and soon after I gained recognition too. I won prizes for my PhD work: first from the language evolution community and then from the British Psychological Society, for the best PhD that year. Soon after the European Human Behaviour & Evolution Association gave me their New Investigator Award, and the British Humanist Association asked me to give their Darwin Day Annual Lecture. Most rewarding of all, people whose work I found inspiring started to show interest in mine.

I won several funding awards to do postdoctoral research and as far as I was concerned this was magic. When I was 12 I told my grandmother I wanted to study Maths at university. “That sort of thing…”, she replied, “..is not for the likes of us.” She’d had very little formal education and her first husband was killed in the war. None of her four boys had schooling beyond age 16. Two generations further on and I was a member of the academy, receiving a salary to push at the edge of knowledge. I was conscious of my luck, living in a time and place where a bright kid from inner city London could, apparently, make a career out of his curiosity.

So I’d done something right and I thought that would put me in demand. In previous jobs, in other sectors, people had asked what was needed for me to stay. But in academia the idea to retain your best junior people, even a subset of them, isn’t seen as good practice, quite the reverse, it’s often seen as weakness because it shows, supposedly, that you’re not being selective enough (“We recruit the best international talent”, is how they put it). Universities can afford this attitude because there is massive oversupply of qualified and able people.

The years after a PhD are demoralisingly unstable. You have invested years in training for no job security. There are far, far fewer good jobs than good candidates. You are on the wrong side of power asymmetries and some senior people are exploitative (one example). Applications for grants and fellowships take many months to be assessed and have low success rates. It is effectively compulsory to change locations for temporary posts of a year or three: a sector wide demand that is against the spirit, even if not the letter, of European employment law. And this happens when important life changes (family, home ownership) are on the horizon. It creates profound uncertainty that puts a brake on your commitment to a place and your ability to build a life. Emotionally it is like trying to navigate a maze where the walls sometimes move when you’re not looking. This is especially so for people working across disciplinary boundaries, who get conflicting messages about what is important. The whole state of affairs is both a strategic and a moral failure on the part of the sector as a whole.

I have not heard enough of today’s senior faculty express outrage at the system they now govern. One or two have confessed discomfort to me in private (“It’s like we’re on top of a pyramid scheme,” said one) but most do not see. If they experienced uncertainty it was in a previous era when the odds were far better. As a result much of the sector’s current leadership have no intuitive feel and too little awareness of their junior colleagues’ reality.

I received some well-intended advice: do some more traditional research. I’d been researching what makes humans a linguistic species but departments of Linguistics recruit linguists and what linguists do is study the interesting detail of languages themselves. Do some research of that kind and then, coupled with my evolutionary perspective, I would be a good candidate for faculty jobs. But Linguistics is a small discipline. There are only about 20 departments in the UK and several are in towns I had no real interest in moving to, so although the advice was ‘good’ in the sense of being true, what I understood was this: having excelled for many years, now I should do different work, tangential to my real expertise, so that in a few years I’ll have slightly better but still not great chances to get an unspecified job in an unknown place where I may or may not want to be.

We must all make strategic compromises sometimes, and actually I would have been glad to follow this route if it came with actual surety, but in practice the only thing on offer was slightly better chances for an uncertain outcome. So I took the only attitude I felt I could. Whatever it was I had been doing had done me well so far.

I led research projects of diverse kinds, collaborating with biologists, linguists, psychologists and anthropologists. This fuelled promotions in rank and salary, a change of institutions and more funding, in particular a Future Research Leaders Grant from UKRI (UK government’s main funding body). But even here I made a critical mistake: to be unlucky with my timing. I won that award the only year UKRI did not compel the hosting university to offer a permanent post. So I had a good thing for a few more years but nothing more. I took the time to write my first book and people said some very nice things about it.

By the time my funding expired, now eight years after my PhD, I could fairly say I was one of the world’s leading experts in the evolutionary and cognitive foundations of language, culture and social minds. I was approached to be Senior Research Fellow on a major project at Central European University (CEU), in Budapest. It had four years to run. I was unsure about another temporary post but there were also clear upsides. I would have several colleagues working in the same scientific tradition as me, and in terms of salary and rank it was another promotion. My relationship had come to an end, and so had the one after that, so the move was good for my emotional health too.

Three weeks after I arrived the Hungarian government moved to evict the university from the country. The next day Theresa May, UK Prime Minister, triggered Article 50 of the Lisbon Convention, formally beginning Brexit. It was my birthday.

Still, Budapest was good to me. We investigated the social nature of the human mind and how it makes and shapes culture. I had PhD students graduate and I enjoyed seeing them advance in their own careers. One is now a leading science journalist, another runs a cultural heritage consultancy, a third won a prize for best dissertation at CEU. I’m proud of the fact that they all made effort, towards the end of their studies, to approach and thank me for the quality and care of my advice. I danced a lot, and once a year friends from all over the world came to Budapest for a week of swing. And I met someone new: we got married this winter just gone. She has her own Substack, innovative playlists of music you haven’t heard before.

Covid-19 arrived and my contract was extended a little. I had employment until the end of 2021, now 13 years since my PhD. I’d held positions in departments of Linguistics, Anthropology and Psychology, and published scores of papers, theoretical and empirical, in leading journals across all these fields. I’d acquired a substantial reputation for big picture, theoretically motivated research. I’d been a good mentor and a good colleague. I’d taught only sometimes in university contexts but when I had my evaluations were stellar. I had, after all, plenty of other pedagogy experience: English as a foreign language, three years in the e-learning sector and 10 years teaching dance in the evenings. I had, if I may say so, all the attributes of an outstanding multidisciplinary scholar.

What I did not have was a stable academic home.

I’ve had my eyes on the job market more or less constantly since about 2008. My fellowships and other funding meant the issue was not always urgent, but I was looking from the beginning. I’ve made shortlists and longlists often, in departments of different disciplines; at institutions from the globally famous to the very small; for posts with greater emphasis on teaching and others on research; and at all career stages from junior faculty to, a few years ago, Director at a Max Planck Institute. But I have always fallen at the decision stage, with one exception that turned into a very painful experience. More about that shortly.

First, some anecdotes of comic unprofessionalism.

After one interview I didn’t hear anything for months. We were in Paris for a few days, where we visited the Shakespeare & Co. Bookstore. Another customer makes eye contact with me and begins to approach. It was that phase of the pandemic when shops had reopened but everybody was wearing masks, so I didn’t recognise him at first. He says hello, moves his mask down and shitting cowbells it’s that guy from that interview panel I never heard from. What is he doing here? (The job wasn’t even in Paris.) Some small talk and then he says, “I’ve been meaning to email you…”: and that is how it happened that in the middle of a bookstore while on holiday in a different country to where the job was, four months after interview, I was told they’d chosen someone else. My partner looked up from her browsing. “Who was that?”, she asked.

A niche job title that describes me well. That fact alone made this a rare opportunity and reading the details it was clear I’d be a strong candidate. Then I saw the list of application documents and it was unnecessarily long and particular. Why deter candidates like this? Still, it is rare to find a good fit at a good university, so I cancelled my weekend plans and prepared everything. Then I waited. I waited months. I waited six months, then I was invited to a 30 minute interview which went ok, albeit not better than that, and at the end I was asked if I had any questions. But before I could start one of the panel added, “..but please be quick we only have two minutes”. They spent six months assessing my documents and I got two minutes to ask them what I might want to know! A few days later I got the rejection email, and the day after that the successful candidate posted their news to Twitter: they were an internal applicant, moving from a temporary position in the same department. Having acquired a permanent post they thanked many people for their support over the years, but singled out in particular their longterm mentor, who was the head of the recruitment panel, THE SAME PERSON WHO ASKED ME TO BE QUICK! Well fuck, that’s why they only had two minutes. It was a pretence. Now I said earlier universities should retain the people they like and I still think that. But don’t waste my time! It is so disrespectful. In a hyper-competitive job market, you are playing games with other people’s time, hopes and ambition. I wrote back, professional but firm. “You have your preferences and I have zero wish to contest them — but I am unhappy about the process.” I got a very short reply, it said that by complaining I had reinforced their view that I did not have the right “collaborative spirit”.

At one institution the interviews were all one-to-one and one-to-two, with the existing faculty.“Thom,…” began one, “..I’ve been told we have to talk for an hour.” Soon this person was telling me how my work compares unfavourably with one of their colleagues. I asked a question to try to find some common ground but was interrupted, “I’m the one asking the questions.” At the end, when I did get to ask something, I was told it was “..a bad question, and I think you have a vested interest in asking it.” This is all bullying and harassment and I would have lodged a formal complaint, but it was just my word against theirs. This is why you should not run one-to-one meetings in recruitment.

But at least that person turned up, one of their colleagues didn’t even do that. “They think they already know enough about your application”, I was told by the one person who did attend. “I hope that’s ok.” What can I say? Of course it is not ok. People are often blind to the humiliations they inflict on others.

It is not always like this, of course. Occasionally interviews are even wholly positive, so let me give some credit where it’s due. At Nottingham Trent the interview felt less like a test and more a conversation well designed to elicit the most useful insights about the candidate. They’d thought about how to remove the artifice of an interview setting. They decided against me but I got a note to explain: when they developed the post they had in mind a particular profile. I was not it but I was also, they could see, a distinctive and unique opportunity they wanted to explore. They came close to an offer but ultimately they chose to stick with Plan A. Which is fair enough: the strategically sensible thing to do. So I did not have a job but this was still a good experience.

What happens most often is they like me but I don’t fit. When I ask for feedback it is almost always some variety of “Very impressive but not right for our department”. At one institution I applied to both the Psychology and the Linguistics panels of a university wide search. Shortlisted by neither, I asked for feedback and the Psychology panel said (I paraphrase), “You were a strong candidate but we think you belong with Linguistics”. The Linguistics panel said (I paraphrase), “You were a strong candidate but we think you belong with Psychology”.

I have learned, over time, that I have two dispositions that are far less common than I once assumed. First, I am a humanist and my curiosity is driven by almost theological concerns: Who are we? Why are we here? Why does it feel the way it does? I am firmly committed to answering such questions with the tools, discoveries and insights of science, and I believed there was space for this in the academy. Second, I am theoretically oriented and good at piecing things together. As a boy I loved logic problems and as a young man I chose mathematics. My career has combined these two dispositions: I want to use and connect the findings of many research programs to answer, better than before, eternal questions about the human.

I was slow, far too slow, to appreciate how this agenda is out of step with the times. For several years I was simply confused, believing that my motives were widespread when in fact they are rare. I was shortlisted for several major grants and was not explicit enough, in my own mind and therefore in my applications, about what made me distinct. I did not appreciate my own difference. I assumed that job panels would see how my broad curiosity and diverse pedagogical experience are assets, for teaching as well as for research.

As an undergraduate I was inspired by stories of mathematical synthesis. Euler’s formula, for instance (eix = cos x + i sin x), identifies a deep and surprising relationship between geometry and calculus, which are otherwise quite distinct branches of mathematics. Later I learned about the synthesis of evolution and genetics. These two areas were once seen as being in tension with one another, because evolution is gradual and genetic inheritance is discrete. When this tension was resolved it was treated, rightly, as a major advance that led to better and more unified understanding. (The key is to distinguish the individual level of analysis from the populational level.) My ambitions have always been to advance knowledge in similar ways.

I led and collaborated on some cool experiments, making new discoveries,1 and I enjoy that work very much; but the outputs I am most proud of have that synthetic dimension. I outlined how a paradigm for communication links with theories of grammar, leading to a clearer conception of language itself. I have been a pioneer in using of philosophy of language to understand how non-human great apes, such as chimpanzees, interact with one another. This helps to explain why they are not “language ready”, as humans are. I connected cognitive psychology with evolutionary theory with to explain why human communication is open-ended; and with art theory to help understand how and why people find meaning in modern art.2 Is this sort of scholarship something we want?

I was once asked “Does this lead to experiments or is it just a return to old philosophy debates from the 1970s?”. Another time, “Doesn’t all this theory have to lead to experiments at some point?”. I once had a paper rejected from a theory journal because the paper “does not propose any new experiments”. A theory journal! I was not shortlisted for one job because “Our department is empirically oriented… people could not see you developing a strong psychological research programme.” Thing is, when I got this feedback I already had a strong, empirically oriented psychological research programme. It’s just that the main goal of this research programme was not new experiments, it was synthesis and better understanding of empirical findings already uncovered. But that is not what this person meant by “psychological research programme”.

I like this line from Henri Poincaré, a 19th century polymath: “Science is built up of facts, as a house is built of stones; but an accumulation of facts is no more a science than a heap of stones is a house”. It is an excellent metaphor. Too many psychologists seem to have the idea that the main goal of theory is to suggest new studies: like saying the main goal of building is to create new stone quarries. Don’t get me wrong, new and better ways to mine stone are obviously essential for future progress, but we build for many other reasons too. It is unserious to imagine otherwise.

In recent years there has been growing diagnosis of deep problem in today’s psychological sciences: not enough attention on theory, frameworks, paradigms and synthesis. Papers making some version of this point are practically a genre by now,3 but my favourite predates the current discourse: it’s this, from 2001. It observes how, in a rush to establish itself as a ‘proper’ science and to distance itself from pseudoscientific enterprises such as phrenology, Psychology has been too quick and too keen to adopt the trappings and the appearance of an old and mature discipline. Here is a composite of key points:

“much of the current field… has an unnecessarily narrow focus… concentrated on the advancement of a formal, precise, and experimental science. However, unlike the successful work in the natural sciences… [this] has not been preceded by an extensive examination and collection of relevant phenomena and the description of universal or contingent invariances… Though some may take pride in the advanced state of the field as measured by increasingly sophisticated statistical techniques, greater experimental sophistication, frequent invocation of models,… one can also be disturbed about these same developments… Premature advanced science stifles creativity, closes the eyes of the field,… is prone to generate long lines of research that ultimately have little to do with the basic target,… and generally pulls people prematurely away from the real world, where it all starts.”

These problems have not receded in the decades since. On the contrary, they have, in my estimation, deepened and spread, like a cancer. Future historians of science will debate how and why this happened.

The most devastating rejection was from the place where I was already employed. A few years after I moved to CEU they advertised new faculty posts in our department. Some colleagues very much wanted me to join the faculty, indeed my appointment would have maintained a teaching and research profile for which we had a strong reputation. So I made the shortlist but the final decision was for a “more traditional” direction. This hurt for many reasons but most fundamentally because it crystallised the problem. By now I had spent 15 years looking for the right opportunity and I thought this was it. I had strong fit, I had been a good colleague and I had institutional knowledge. But preferred methods won out: three more experimental psychologists.

I approached two philosophers I know for career advice. Would I have any chances there? What might I do to enhance my prospects? Each answered the same: it would not be wise to orient that way. They both believed Philosophy would gain from having people like me around, but without a formal background in the field other philosophers would not recognise me as one of them. A farce proved this right. A friend sent me an advert for a post in Philosophy at her university, and it read like they were thinking of me. They wanted someone to teach and research on the cognitive and evolutionary foundations of language, from a theoretical point of view — but the advert said a PhD in Philosophy was a formal requirement. My PhD is in Linguistics, in fact it’s on the cognitive and evolutionary foundations of language, mostly from a theoretical point of view. So I emailed them and they replied no, the rule is the rule. Since the certificate I got more than a decade ago has the wrong word on it, my application would automatically be ineligible.

Last summer the British government released several thousand criminals early because prisons were literally full. Trials were being delayed because there was nowhere to send the newly convicted. This problem has been known about for years and, when asked, every UK politician will say we must build more prisons. We must build new prisons! But those politicians also all represent specific constituencies and they will also say oh, no, the new prisons shouldn’t be here, not where my voters live. Well, virtually all academic posts are situated within specific departments and we have the same problem. Everybody says we need new ideas and more synthesis across disciplinary boundaries, but then they’re on a job panel and they get an application from someone who has spent their entire career doing that, and someone will say oh, no, that’s not right for this post. The philosophers want ‘proper’ philosophers, the linguists want proper linguists, the anthropologists want proper anthropologists, the psychologists want proper psychologists, but the one thing everybody agrees on is that we must support unorthodox career paths. We must support unorthodox career paths! It is institutional hypocrisy, and it stinks.

And then three weeks before my post at CEU expired, 17 years after I started my career, I got an offer. A permanent post (or so I thought). The news was in capital letters in the subject line. SELECTED.

Ikerbasque is a project of the Basque Government. There are some differences but it is similar in spirit to systems in France (CNRS) and Catalonia (ICREA). The government employs the researchers, so they are technically civil servants, and they are based at one of the research institutes or universities through the region. I had applied through the Institute for Logic, Computation, Language & Information (ILCLI), in San Sebastian.

The body of the email I asked if I was still interested. I replied yes, of course, and they sent me the formal offer. It was not what I had applied for.

There are two grades of permanent post in the Ikerbasque system: Associate and Professor. The call for applicants was explicit that somebody of my experience would be appointed as Professor. And indeed, I had held a position “comparable in terms of scholarly qualifications and appointment to a Professor” for the past five years. I also had a more prominent research profile than current Ikerbasque Professors in my areas. But Ikerbasque offered Associate and did not explain why. I felt very deceived.

They were also offering a 25% pay cut. Russia had recently invaded Ukraine and inflation was over 10%.4 I would be up for evaluation in three years and if I passed I would get a below inflation pay rise. Over email I asked the professional question about future progress. What I should add to my CV in the coming three years, in order to secure a positive evaluation at review? I did not even get a straight reply, just this: “We’re sure you’ll have a good career with us.” No te preocupada, as they say.

I suspect there was some cultural gap here. I suspect there are some important aspects of how academics are assessed in Spain and the Basque Country that I was not alert to and hence did not flag as clearly as I could. But still: I am baffled why an organisation would actively present itself as internationally oriented and spend significant effort and money to recruit from far and wide, to then, having identified who they want to recruit, offer a demotion and a pay cut and not even tell the new recruit what the problem is or how it could be addressed. It is completely self-defeating. New recruits coming from outside will not settle.

But my current job was fixed-term and expiring, so my choice was now and it was this. 13 years after my PhD and after everything that had gone before, I would move to new country to join an organisation that had misled me, offered a pay cut and no clarity about how to go forward; or otherwise I could let go of my income and career. I had hoped to tell my parents that I had become a Research Professor, a job title they could not dream of when they started a family in the 1970s with little money and no higher education of their own, but the actual news was that I had such little bargaining power that I was accepting a career demotion and I was moving to a place where I had no roots in order to do it.

The most persuasive ideas I’ve read about happiness say it comes from a sense of going forwards: from advancement. The extremes show this most clearly: major positive life events have a sense of forward change (marriage, children), traumas have the opposite (divorce, deaths). Most change is small but the important thing is not scale, it is direction. Happy people are those who find a sense of advancement on the regular. And this is why when you undermine people they become less productive. They’re not protesting, it’s because they have a sense of going backwards. That makes them unhappy and that means they will work less hard. This will especially be a problem in sector that runs on intrinsic motives, like academia.

All of which is to say: I was shocked how demotivated I became, and how quickly. The hit was almost physical. I’ve always been driven by scholarship and this new post did still have the major upside of time and space to do that. And of course, sometimes in life you should accept some downside to bring upside elsewhere; but this had arrived in a misleading, opaque and frankly disrespectful package, and for the first time I had regular bouts of not giving a fuck. In the meantime many of my friends and peers at other institutions went forward, gaining promotions and opening new doors. I was pleased for them and they deserved it, but the contrast was pain. I tried to look at social media less often, it hurt when I did.

Then I learned my post wasn’t even properly permanent. A bureaucratic barrier demanded a creative solution, the upshot of which was that I was to be 60% employed on a permanent contract and 40% on a 1-year contract, with the shared understanding that this 1-year contract would always be renewed. Nobody seemed to note that with this arrangement I did not actually have the legal security that should come with a permanent post; or that this arrangement would complicate any mortgage application and how that might prevent me from staying over the longterm. Nor had anybody told me any of this before I applied.

So I was already frustrated and then administratively things were awful. I don’t want to bore you, reader, with bureaucracy, nor do I want to prosecute the past, this essay is not about that, but I do want to explain why I later resigned, so some highlights. When I arrived there was no internet access and no computer for me, not even a temporary one. As in: literally no means with which to do the job. It took several months for the necessary bureaucracy to be worked through, and the leadership suggested that I should, in the meantime, contact my previous employer and ask if I could use the laptop and internet access from that post. This was intended as a constructive suggestion and indeed from a practical perspective it was the only option, but there seemed to be no awareness of how unserious this was. There was also no swipe card for my office, so for the first week whenever I went to the toilet I had to check in with colleagues just to avoid getting locked out.

The dedicated housing that is advertised to help settle new Ikerbasque researchers had no space for me. Ikerbasque refused to use my existing EU bank account because it was not Spanish: this is straightforwardly illegal and I (politely) pointed that out,5 but they still insisted. There was no induction process of any kind and the institute has no administrators of its own, so I was always having to ask around and ask favours, unsure how even basic things worked. The nearby PhD students were good to me but it should not come to that: my needs are not their problems. Then the expenses system was opaque and traumatic. I spent several days trying to register with it and submit a claim for €800. Twice I was told everything was in order and twice it never came. Nobody ever contacted me to tell me of a problem, the money just didn’t come. In the end I gave up so I lost the €800 as well as my time.

Successful academic careers are clearly possible in Spain and the Basque Country, because some people are doing it. But there were zero processes necessary to integrate and support incomers, and as an outsider already disillusioned I did not have the patience or energy (nor yet the language) to teach myself how things work. My immediate colleagues were friendly, but sympathy and open doors are not substitutes for a proper induction process and clear points of contact.

Then suddenly, one Sunday night, these many frustrations were placed in perspective. Again the news was in capital letters in the subject line. CALL ME NOW. It was from my Dad.

Mum had had a major stroke, a haemorrhage in her brain. I feared she’d be gone before I could get to London, but as things have turned out she’s still with us now. She spent two months in intensive care, and recovered back in the hospital where she gave birth to her two boys. On my first visit after she woke up she peered at me. “I know you, who are you?”

“I’m Thom, I’m your son.”

“Yes, yes you are”, she replied, some recognition appearing on her face.

So I started dividing my time three ways: Budapest and Vienna, where my partner was; San Sebastián, where work was; and London, where Dad and my brother were tending to Mum.

When in Spain I was lonely. San Sebastián is a great place for a holiday but it is also poorly connected, five hours to Madrid and a minimum of two flights and 18 hours to Budapest. It has the most expensive housing in all of Spain (the consequence of bringing Airbnb into a small and pretty place) and the dance community is little. I knew almost no-one, and now I was coming and going.

I became increasingly, even deeply unhappy. I could not shake my anger: at the sector in general and at my present employment. I began to lose a lot of sleep. Every other night I would wake at 3am and lie in the dark repeating past incidents over in my head. Sometimes it was the whole night. For the first time in my life I started to gain serious weight, and then I began to have thoughts I hadn’t had since I was teenager, about self-harm and suicide. I was never close to doing anything unwise, I have good people around me and I am old enough to recognise these things for what they are; but still, I’d done good things and pursued original ideas, I’d been industrious and had a lot of success, I’d pulled my weight, I have all the skills, yet the only employment I could get was under these unhappy circumstances. It was extremely hard not to dwell on this fact.

Then I’d log on and I’d read stories about unprofessionalism and worse, about professors who ignore, belittle or, even worse, bully their students; who exploit asymmetries of power; who fake data; who hype thin and shallow work; who waste millions in research funding — and they still have good jobs! What message does it send? The market is hugely competitive and honestly, cheating and cynicism look like good bets.

Another job interview. By this time I was in a bad state of mind and the night before I had a wholly sleepless night: this was now happening every week. So I was very tired and not sharp, I did not give good answers to questions that should have been strong points, and that was another rejection. There was another a few weeks later.

If only one thing in Spain had been better (the pay and transparency, the bureaucracy, the travel connections, the dance scene) me and my partner would have made it work. She will soon reach a transition in her career and my post was a potential anchor for our long term plans. But the facts on the ground were leading me to deep sadness and rancour, and I could not tolerate the pain any longer. So I finally did the one thing I knew would give me release, and that night I slept the best I had in months.

I’ve continued with scholarship in the year since, but I am much less angry now, and that means I get to sleep.

I finished some papers I’m especially proud of. I led a summer school on The Human Mind & The Open Society, we run another iteration this year. I dug deep into the history of the lindy hop and its roots in the Harlem Renaissance. Last year I was awarded another prize, for the best paper of the previous year “exemplifying the adaptationist program”: the scientific idea that had inspired me to become an academic in the first place.

For a while job hunting and grant applications were a full time occupation. Each country, each scheme, each discipline and each department, they all have different wants and expectations, and I spent a lot of time, too much time, crafting applications. One post in particular was an excellent fit and the interview mostly went well, but at one point the head of the panel asked, “Don’t we have to move on from this stuff?”, by which he seemed to mean theoretical analysis. I heard on the grapevine that I was very close to getting the post, but in the final analysis they chose an experimentalist. Of course they did.

So that well-meaning advice I got right back at the beginning was right: be more traditional. Many, many people have said to me, at some point, “There’s no way you won’t get a good job somewhere, not with your track record,” but those people were wrong, and if I have any wisdom to share with young academics now, it is this: (1) be lucky; (2) make sure you excel in orthodox ways, even if there are other strings to your bow.

I feel very much that my life’s work is unfinished. So just in case you’re a rich patron looking to sponsor a Professorship somewhere, here’s the pitch. In 1905 Albert Einstein had his Annus mirabilis. Having cracked important problems about the connections between space, time, mass and energy, he published four major papers on the foundations of physics. I’ve recently cracked important problems about the connections between evolution, communication, meaning and grammar, and if you back me I’ll produce a Decennium mirabilis: dozens of major papers on the foundations of language and culture. I’m not joking.

I am very bruised but I still have my motives and I have a great deal to share. I have a lot to say about how evolutionary and cognitive perspectives help us understand ourselves and navigate the world today. I have pursued that agenda in one way and now I will pursue it a different way. I will begin here, on Substack: regular essays about language and communication, modernity and the evolved mind, great apes, the philosophy of science, the lindy hop, the challenges of psychology and much, much more.

Much of this work was in collaboration. Thank you to Christophe Heintz, Kate McCallum and Scott Mitchell.

I knew that the salary in Spain would not be as competitive as elsewhere in Europe. However, it had been some years since I’d had a raise, so I anticipated that the advertised position would be roughly similar in nominal terms. I pushed back and they increased the offer a little, but in real terms it was still a 30% cut.

It’s called IBAN discrimination.

My goodness, Thom! The subset of your work that I know is so important, and so damned excellent. From half a world away I had no idea about this. You lay out so much of what is wrong in how organisations recruit and how disciplines coalesce. For all the suits who cap on about “breaking down silos” but build budgetary units =structures that reify those “silos”, you’d think there would be tried and workable ways that every institution has to make better hiring strategies happen. Everywhere!

Thank you for this really important and yes awfully sad post!

I fear this is a reflection on humans, rather than on you Thom. Other sectors have analgous dysfunction, very good people get treated abominably. I'm not an academic but have been avid in trying to get to the bottom of big questions and your papers were key parts of the jigsaw. That you have not gained due recognition is shocking. Wishing you health and success.