How I learned to stop worrying about bad reasons

Like so much of the human mind, reasoning is ultimately a social trait.

We’ve all experienced other people’s bad reasons. You’re so biased! Why can’t you see the problem?! It’s very annoying. Why are they like that?

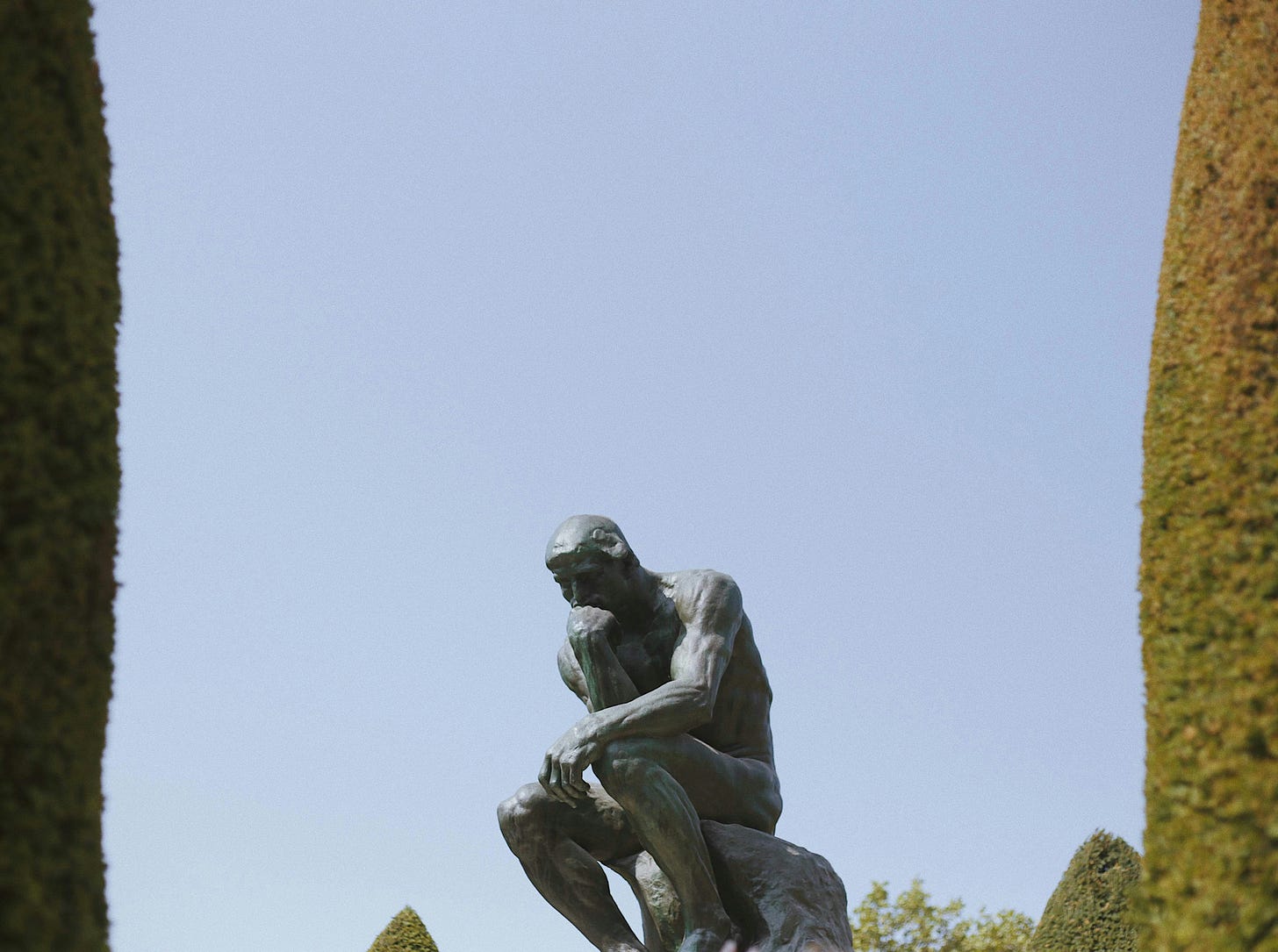

The psychology of reasoning has long history dating back to ancient Greece. Throughout, it’s been largely unquestioned that the primary function of human reason is to help us get closer to truth. This Enlightenment idea is often called ‘Cartesianism’, following René Descartes' arguments for the privileged status of reason as a source of knowledge. It’s made graphic in Auguste Rodin’s famous sculpture ‘The Thinker’, which depicts a single individual deep in thought, fist on chin.

But there’s a problem for this unquestioned assumption: humans aren’t actually very good at plain, individual reasoning. (Descartes may have been, but most people aren’t.) People are clearly prone to biases and logical fallacies that are formally quite simple. The most well known is confirmation bias: the tendency not to evaluate information on its own objective merits, but instead to search for, interpret, favour, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports your prior beliefs. As author and comedian Jon Ronson put it, “Ever since I first learned about confirmation bias, I’ve been seeing it everywhere”.

Confirmation bias is not a one-off. Behavioural economists have documented many such ‘failures’ of reason at some length. Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler were awarded Nobel Prizes for doing so, and for articulating the implications of these ‘failures’ for the assumptions and models of classical economics.

So there’s a paradox here. If Descartes is right and the function of reason is to get closer to truth, then why are we prone to simple fallacy? In any system designed to improve knowledge through individual, rational thought, confirmation bias is a clear flaw. Let me make the point graphic. It’s like aiming to build a utensil for putting food in your mouth, and ending up with a knife. Yes, you can hold it in your hand and yes you can pick up food with it. It has something to do with eating. Still, something is clearly not right. It’s awkward to balance food on it and that sharp edge looks dangerous. Presented with a knife for the first time, you would never conclude that its primary function is to help you put food in your mouth.

By the same logic, confirmation bias and other such dispositions should invite us to consider that the function of our reasoning skills is not to help individual thinking after all. Reason can be used that way, just as knives can be used to feed, but it doesn’t seem to be designed for that purpose at all.

People sometimes complain that psychology hasn’t delivered many fundamental and substantive advances in our understanding of the universe. A while back Paul Bloom (Small Potatoes on Substack) tweeted to ask psychologists what they thought were the major discoveries of the past few decades. Adam Mastroianni (Experimental History on Substack) was one of many readers underwhelmed by the replies, which gave him “a deep sense of despair”. I agree that much contemporary psychology is thin and unimportant (and too often it is flat out wrong). But there are a few great ideas out there and I replied to Paul to mention one: “The communicative principle of relevance”. Too few psychologists know about the communicative principle of relevance and even fewer understand it well: so more about that in a future post.

If I’d sent a second reply it would have been: “The argumentative theory of reason”. This is a big deal: a major advance in our understanding of human thinking. Among other breakthroughs, it resolves the paradox I outlined above.

The argumentative theory of reason says that the function of reason is not what everyone had hitherto assumed it to be. Reason is not for getting closer to truth. Reason is for justifying, persuading, convincing and critiquing. Like so much else about the human mind, reason is social.

The features of a knife, like a handle and a sharp edge, tell us that knives are for cutting. The features of a rib cage tell us that they are for protecting internal organs. That’s why it’s called a ‘cage’. And the features of human reason tell us that what it’s for is persuasion and critique. Think again about confirmation bias. If the goal is to persuade others, then a built-in propensity to search for arguments that support your existing view is just what you need. Tasked with building a system to generate arguments that persuade others in communication, confirmation bias is exactly what you would build! Confirmation bias is not a ‘failure’ of reason. It’s good design.

Reasoning coldly and rationally is certainly possible and very useful, but it is an acquired skill, akin to, say, lifting heavy weights. Particular individuals can become highly competent. But they also have off-days, they are prone to regress if the skill is not practiced, and strong institutional support—gyms for lifting, schooling for reason—is necessary if the skill is to become widespread and stable in the population at large. In contrast, finding reasons that might best persuade others is like walking. Walking also entails moving something heavy (your own body), but in this case the task is easy and natural because our bodies are built to do it. The science of anatomy has revealed how our bodies have features specialised for the task of walking (muscles, bones, joints), and the science of thinking has revealed how our minds have features specialised for the task of arguing, persuading and critiquing what others have to say.

When you start to look at reasoning in detail, what you can see is that human reason has many attributes that would be bugs if the system was designed to serve the rational pursuit of truth, but which are actually features, if the goal is argumentation. Here is another example: when faced with a choice between a conclusion that is true and a conclusion that is easy to justify, we tend to go for the latter over the former. Justification trumps truth. It’s good when what is true is also what is most easily justified, but these two things do not always overlap and when they don’t, we tend towards the latter. If you’re a Cartesian then this is a plain flaw in human thinking, but from the perspective of the argumentative theory, this tendency appears now as good design. If the goal of reason is to persuade others in interaction, then justification is the top priority.

The argumentative theory of reason has helped me understand some things about humans that I didn’t understand before. I see now how the many supposed ‘biases’ of human thinking are really byproducts of social dispositions and motivations. I also get why two heads are better than one: it’s because discussion and deliberation are the natural ecology of human thinking. This point is important and after I understood it I started reading up on deliberative democracy. I ended up writing a paper, ‘Human nature & the open society’, about how deliberative forms of government go with the grain of human reason.

When people offer bad reasons it’s very tempting to see them as dishonest. Nobody is stupid enough to think what you seem to think. That reaction is Cartesian in spirit, because it treats bad reasons as an aberration: as deviation from what reasoning is ‘meant’ to be about. But now I don’t think that’s right at all. Now I think that more often than not, people offering bad reasons are just sincerely wrong. It’s not that they know the truth and are lying. It’s more that they are mistaken about the truth and this is the best they’ve got! If they had good reasons they would have found them, but they didn’t so they don’t.

So these days I don’t get so annoyed by other people’s bad reasons. In situations where I’m confident others are wrong, I sometimes used to become frustrated, even angry, because I saw their mistakes as disingenuous. Not so much anymore. Maybe I’m just a bit older and more chill, but I also think I interpret bad reasons differently. What the argumentative theory of reason has taught me is that the best explanation of other people’s stupidity is just that they’re sincerely wrong and they’re offering up the best they have. Which is good to know because it’s doesn’t make me angry. Now I can just ignore them.

This is a good article. I found it because I'm writing about the interactionist theory of reason too. Reading "The Enigma of Reason" completely changed how I think about thinking!

In my experience, most people's mistakes of reasoning are unintentional, as you say. And it is also true that philosophers and others that dedicate time to reasoning are good at spotting fallacies and other mistakes. But it's worth noting that philosophers are certainly not immune. Kant even dedicated a large part of the Critique of Pure Reason to identifying and diagnosing some incredibly persistent errors in reasoning he found in the history of metaphysics (the Transcendental Dialectic). So, I think we can extend your conclusion to include professional thinkers as well: we might assume that philosophers are guilty of rhetorical or disingenuous use of bad reasoning to support their pet theory, but I think there's a good chance that they too are unaware of some of the mistakes they make.